To coincide with The Death Detectives, an event taking place at TPG on Thursday 3 December at 18.30, we have invited the speakers to contribute their thoughts around the theme of Death to our blog. First up is Elizabeth Cotton.

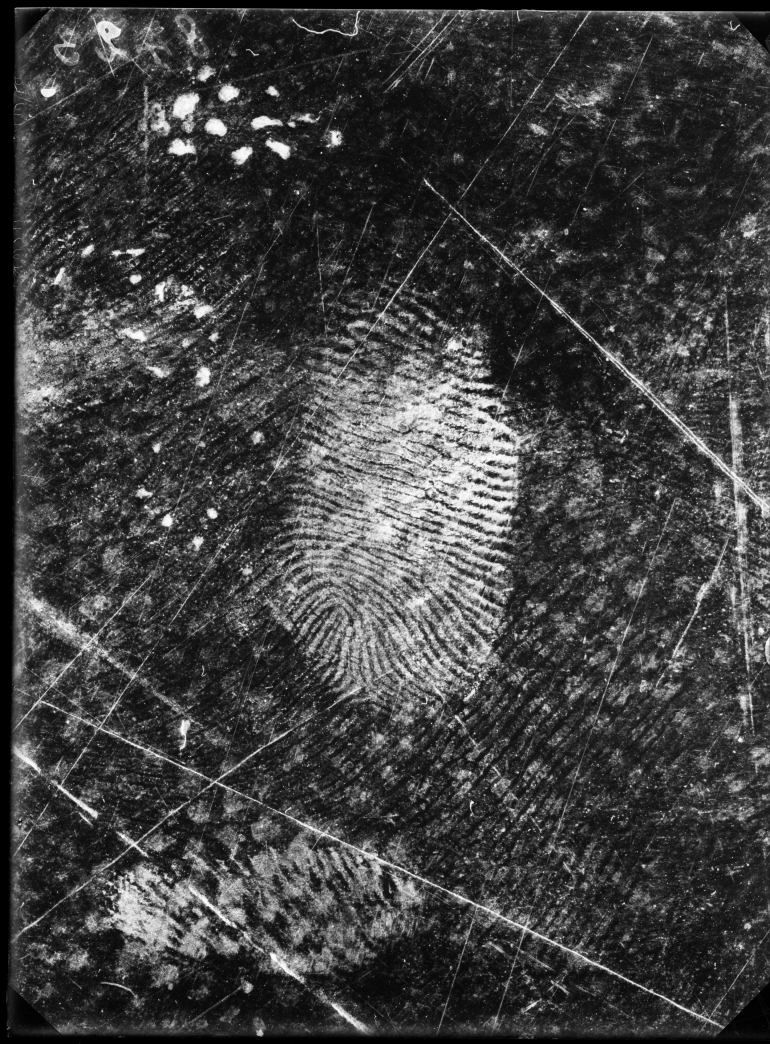

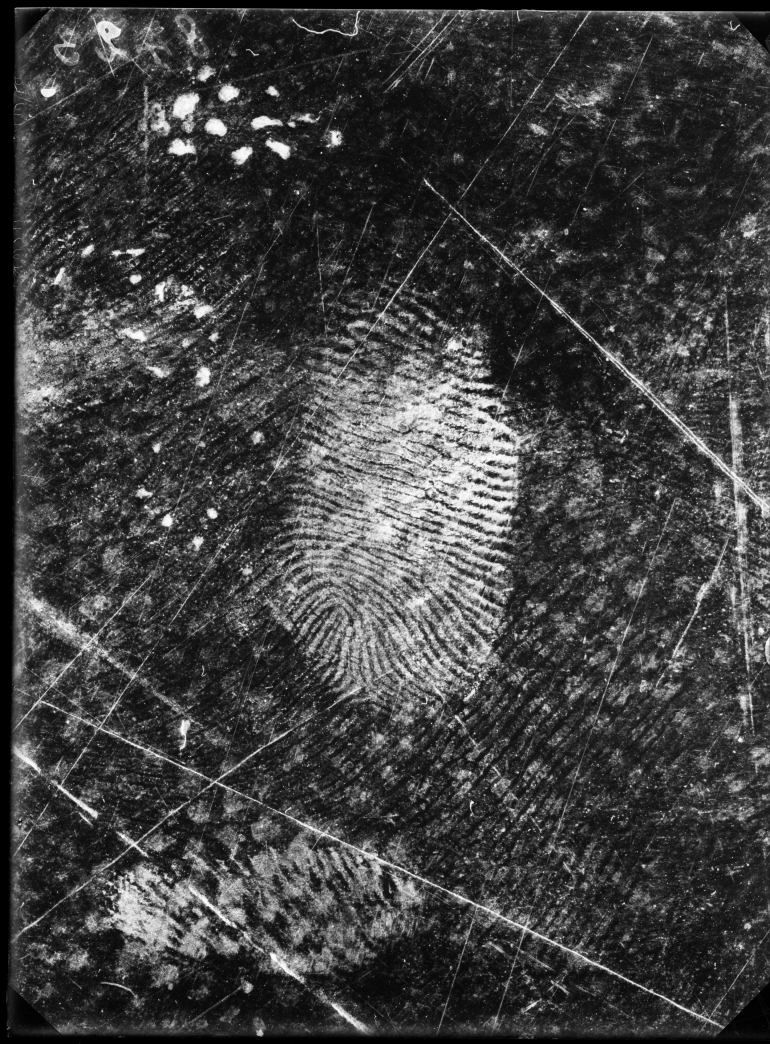

Rodolphe A. Reiss, Fingerprints found on oilcloth, Jost Grand-Chêne case, Lausanne, 25 November 1915. Collection of the Institut de Police Scientifique et de Criminologie de Lausanne. © R. A. REISS, coll. IPSC

The Death Detectives is taking place at The Photographers’ Gallery in London on Thursday – an event to talk about, erm, death. This is the fastest selling event in the Gallery’s recent history, something you would not have put money on. Since when did a bunch of psychoanalytically-minded folk staring into the abyss attract such a crowd?

Freud talked about the practice of psychoanalysis as like the work of a detective. Fragments and remains – unconscious and conscious – offer us evidence for the stories of our lives that have become obscured. Investigating the details of the psychic crime scenes a way to uncover our reality.

Forensic photography, like psychoanalysis, aimed to develop a protocol – the rules by which photography can be considered factual and providing evidence. The scientific nature of such protocols is contested terrain in both photography and psychoanalysis, whether links can be made between the forensic details to the now hidden course of events.

Walking through Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence at The Photographers’ Gallery, the parallels between psychoanalysis and forensic photography are striking.

The father of forensic photography, Alphonse Bertillon, working as head of photography for the Paris police force, developed the first protocol for systematically recording the crime scene – using a technique of Photographie Metrique. Using a tripod to photograph a bird’s eye view, the victim is placed in the middle of the picture, with all the details of the scene given equal attention. A non-judgemental perspective. The photographs are surrounded by a metric ruler, to measure the relative distance between these details. This includes a simulated wooden ‘sill’ at the bottom of the page, a tender attempt to formally frame the crime; to contain the violence of the images within.

This forensic perspective speaks to the position of the patient under the analytic microscope. Sometimes experienced as a cold autopsy, the blood and guts of the psychic investigation – analyst as pathologist. While at the same time the objectivity of the protocol creating a space for a benign observer, someone to cooly make sense of the psychically raw data.

In the next room of Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence is the abstract work of Rodolpe Reiss – Bertillon’s student – who set up the first forensic school at the neutral University of Lausanne. The images in this section are close up abstract images of the details of crime scenes. A blood splatter on white fabric, a folded handkerchief, scratches on a dark floor. For such scientific images they profoundly draw the viewer in – demanding us to understand them.

This attention to detail is paralleled in psychoanalysis – the insistence on the significance of the small things; that a mark on the body or a dream, if interpreted can uncover real meaning in the world. They are both systems that accept the truth of the details and their relevance to understanding the human story behind them.

This is a further link between forensic photography and psychoanalysis, the necessity of the detective’s work for us to interpret and make sense of the details as part of a bigger picture. The proposal of The Death Detectives is that however factual the data is, ultimately it requires interpretation. Someone always has to understand what is being shown. This is a profoundly humanistic view, where we are dependent on each other to do this detective work of knowing and understanding reality, including the certainty of death. A human story pieced together by other humans.

This event will take place just two weeks after the Paris shootings. The political and social crisis that November 13th is part of came close to the world of photography, happening at the time of Paris Photo, with many people from the photography world including staff from The Photographer’s Gallery being there. Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence was curated in France – coming out of a powerful French intellectualism, unafraid of conceptualism and complexity. This position that promotes ideas and their everyday use to understand human experience is one that we should cherish.

The Death Detectives event and the eBook that accompanies it, is motivated by the belief that by allowing the knowledge of death into our lives we can live life more fully. Together.

– Elizabeth Cotton

Elizabeth Cotton is a writer and educator working in the field of mental health at work. She teaches and writes academically about employment relations and precarious work, business and management, adult education, solidarity and team working, and resilience at work. She blogs as www.survivingwork.org and @survivingwk and runs the Surviving Work Library, a free resource for working people on how to do it. She writes a bi-monthly column for theconversation.com Battles on the NHS Frontline – looking at the realities of working life in health and social care sectors.